Today, Solar Orbiter is crossing directly between the Earth and the Sun, about halfway between our planet and its parent star, and this allows for a unique study of space weather and the Sun-Earth connection.

The Sun releases a constant stream of particles into space. This is known as the solar wind. It carries the Sun’s magnetic field into space, where it can interact with planets to create aurorae and disrupt electrical technology.Magnetic activity on the Sun, often taking place above sunspots, can create gusts in the wind enhancing these effects.

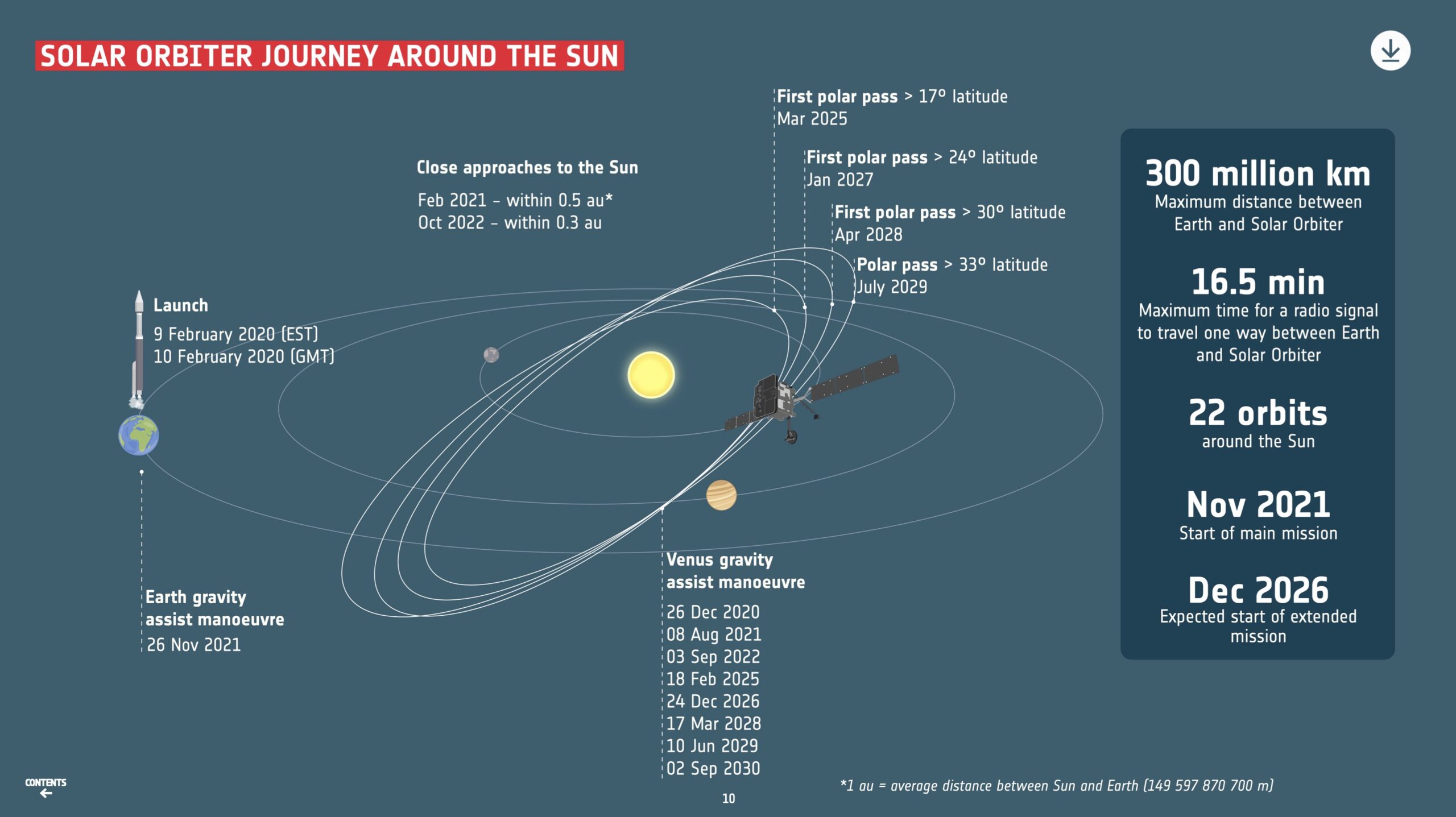

Mission milestones. Credits: Esa

This behaviour is known as space weather, and scientists can use today’s Earth-Sun line crossing to study it in a unique way. They will combine Solar Orbiter observations with those of other spacecraft operating nearer the Earth, such as the Hinode and IRIS spacecraft in Earth orbit, and SOHO, stationed 1.5 million kilometres away from Earth. This will allow them to join the dots of any space weather event as it crosses the 150 million kilometres between the Sun and the Earth.

Solar Orbiter’s remote sensing instruments may also be able to pinpoint the origin of any event on the solar surface. Such ‘linkage science’ is one of the main drivers behind the Solar Orbiter mission. Even if no big event takes place there is still a lot of science that can be performed in analysing the evolution of the same packet of solar wind as it travels outwards into the Solar System.

Because of its position and relative proximity to Earth, Solar Orbiter has so far been able to stay in almost continual contact, beaming back large quantities of data. The processing is happening quickly too. For example, the magnetometer data is processed and cleaned within roughly 15 minutes of it being recorded. The 15 minutes even includes the three and a half minutes that it takes for the signals to cross space between the spacecraft and the ground station.

On 10 February, ESA renamed its upcoming space weather mission from Lagrange to ESA Vigil. Launching sometime in the middle of the decade, the spacecraft will be a solar watchdog, constantly monitoring the Sun for unpredictable magnetic activity so that Earth’s infrastructure, satellites, inhabitants and space explorers can be protected from these unpredictable events.

Solar Orbiter is currently around 75 million kilometres away from the Sun. This is the same distance as the spacecraft achieved during its close pass to the Sun on 15 June 2020 but nothing compared to how close it will now get.

“From this point onwards, we are ‘entering the unknown’ as far as Solar Orbiter’s observations of the Sun are concerned,” says Daniel Müller, Solar Orbiter Project Scientist.

On 26 March, Solar Orbiter will be less than one-third of the distance from the Sun to the Earth, and it is designed to survive this close for relatively extended periods of time. It will spend from 14 March to 6 April inside the orbit of Mercury. Around perihelion, the name for closest approach to the Sun, Solar Orbiter will bring high resolution telescopes closer than ever before to the Sun.

Together with data and images from Solar Orbiter’s other instruments, these could reveal more information about the miniature flares dubbed campfires that the mission revealed in its first images.

“What I’m most looking forward to is finding out whether all these dynamical features we see in the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (coined campfires) can make their way into the solar wind or not. There are so many of them!” says Louise Harra, co-Principal Investigator for EUI based at the Physikalisch-Meteorologisches Observatorium Davos/World Radiation Center (PMOD/WRC), Switzerland.

To do this, Solar Orbiter will use its remote sensing instruments, like EUI, to image the Sun, and its in-situ instruments to measure the solar wind as it flows past the spacecraft.

The 26 March perihelion passage is one of the major events in the mission. All ten instruments will be operating simultaneously to gather as much data as possible.

Solar Orbiter is a partnership between ESA and NASA.

Source: ESA

Watch the video on Esa’s YouTube channel: